Two

Questions

for

Ammiel

Alcalay

Two

Questions

for

Ammiel

Alcalay

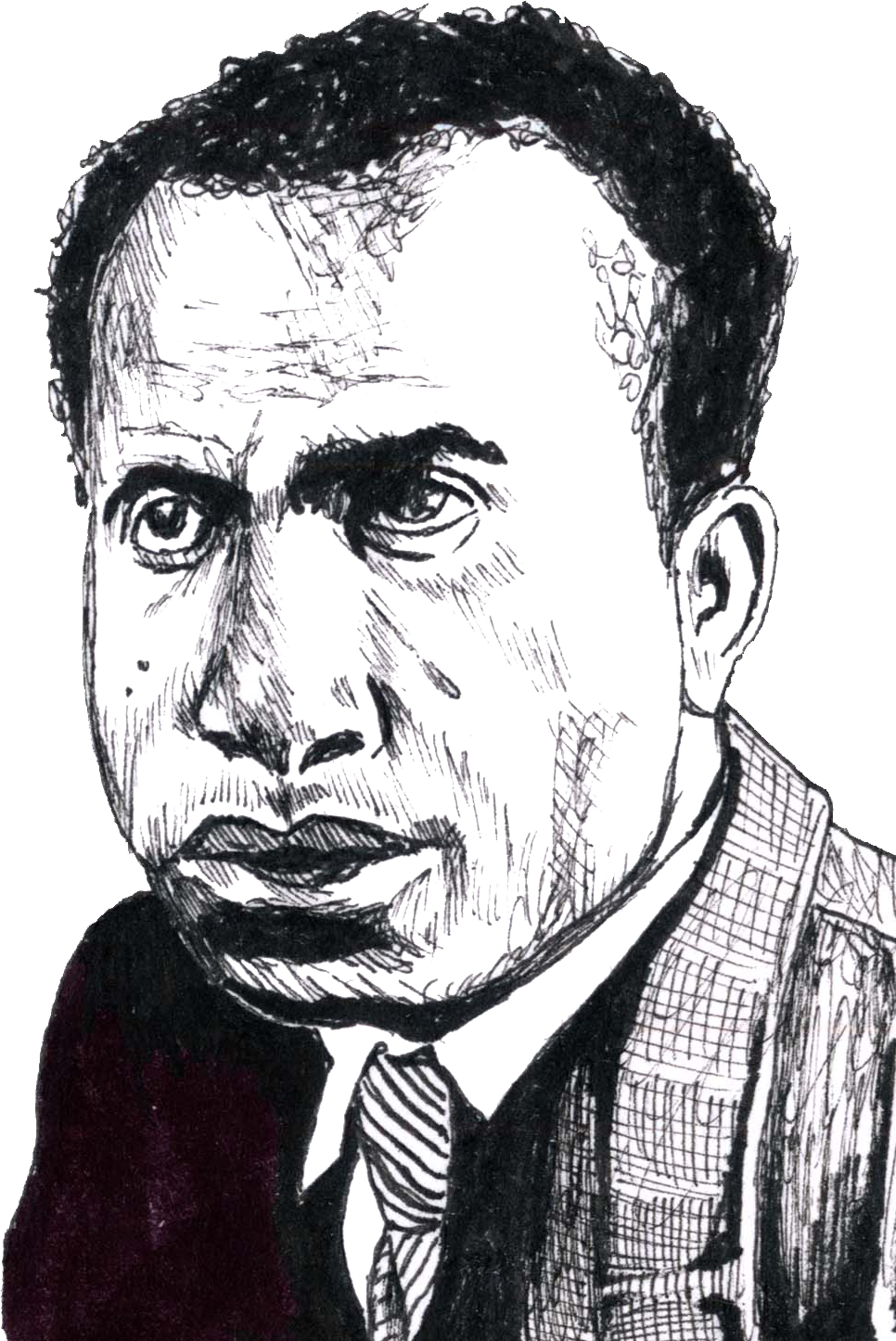

Ammiel Alcalay is a poet, scholar, critic, translator and author of a little history (2013), which examines the life and work of poet Charles Olson against the backdrop of the Cold War.

Charles Olson (1910-1970) was an American late Modernist poet whose unfinished 635-page work The Maximus Poems explores, amongst other themes, humanity’s location from a geo-historic and mythological perspective.

Illustrations by Anya Levy.![]()

Charles Olson (1910-1970) was an American late Modernist poet whose unfinished 635-page work The Maximus Poems explores, amongst other themes, humanity’s location from a geo-historic and mythological perspective.

Illustrations by Anya Levy.

You wrote in a little history that Olson wanted to “write a Republic” and “initiate another kind of nation.” What experiences lie behind this, and where do these interests locate him amongst his contemporaries?

When Olson resigned in protest from the Office of War Information in 1944 over their tacit encouragement of Axis propaganda, I don’t think he was at all alone in the depth of his convictions. But let’s take that moment: 1944– Frantz Fanon was a young, idealist student of Aimé Césaire who enlisted in the French army to spread the universal ideals of France. It took him to Algeria, where what he saw horrified him. The Algerian revolutionary poet Jean Sénac published his first poems in 1944 and Robert Duncan published “The Homosexual in Society.” One could go on.

It’s crucial to identify such moments and their shifting conditions. In the US, for instance, there is an absolute sea change between poets involved in political movements who come of age in the early 20th century and those who begin their work during the Cold War. Many politically motivated poets of the earlier period had venues reaching large audiences, while in the 1950s they would largely need to self-publish to a very small audience.

![]()

In Gloucester, MA, there is a publicly-accessible replica of Olson’s library by scholar Ralph Maud. During a discussion group there on poet Vincent Ferrini, the issue came up that if a little magazine is to be viable, it must have the principles of a republic, with viable political principles at root. At issue was Ferrini’s magazine Four Winds, which first came out in the early 1950s.

Olson first noticed Ferrini through his poems in the small magazine Imagi. Ferrini had grown up the child of immigrant Italians who worked at shoe factories in Lynn, south of Gloucester. A member of the Electrician’s Union– and briefly the Communist Party– while working for General Electric, Ferrini was hounded by the House Un-American Activities Committee and so left Lynn for Gloucester months before he would have been eligible for a pension.

That Olson then reached out to Ferrini is interesting. My hunch is that, following stints at Wesleyan, Harvard, the Office of War Information, and visits to poet Ezra Pound at St Elizabeth’s psychiatric hospital, Olson felt he was betraying his working class, immigrant background. That discussion group was a rare occurrence, being far from academic, with Gloucesterites of different backgrounds and ages coming together to discuss Ferrini and his relationship to Olson. So, not having found a republic, there was still a place made for poetry in that small city.

Such encounters are becoming rarer: moving from analog to digital interfaces, there are fewer “free” spaces. I think, for example, of W. Eugene Smith’s Jazz Loft Project, a building on 28th st. and 6th Avenue in New York City in which, from 1957 to 1965, all the assumptions about race relations in the US were blown apart by the presence and interaction of the most important musicians in the country. I do still think that the creation of any kind of politics has to begin someplace, literally.

When Olson resigned in protest from the Office of War Information in 1944 over their tacit encouragement of Axis propaganda, I don’t think he was at all alone in the depth of his convictions. But let’s take that moment: 1944– Frantz Fanon was a young, idealist student of Aimé Césaire who enlisted in the French army to spread the universal ideals of France. It took him to Algeria, where what he saw horrified him. The Algerian revolutionary poet Jean Sénac published his first poems in 1944 and Robert Duncan published “The Homosexual in Society.” One could go on.

It’s crucial to identify such moments and their shifting conditions. In the US, for instance, there is an absolute sea change between poets involved in political movements who come of age in the early 20th century and those who begin their work during the Cold War. Many politically motivated poets of the earlier period had venues reaching large audiences, while in the 1950s they would largely need to self-publish to a very small audience.

Frantz Fanon

In Gloucester, MA, there is a publicly-accessible replica of Olson’s library by scholar Ralph Maud. During a discussion group there on poet Vincent Ferrini, the issue came up that if a little magazine is to be viable, it must have the principles of a republic, with viable political principles at root. At issue was Ferrini’s magazine Four Winds, which first came out in the early 1950s.

Olson first noticed Ferrini through his poems in the small magazine Imagi. Ferrini had grown up the child of immigrant Italians who worked at shoe factories in Lynn, south of Gloucester. A member of the Electrician’s Union– and briefly the Communist Party– while working for General Electric, Ferrini was hounded by the House Un-American Activities Committee and so left Lynn for Gloucester months before he would have been eligible for a pension.

That Olson then reached out to Ferrini is interesting. My hunch is that, following stints at Wesleyan, Harvard, the Office of War Information, and visits to poet Ezra Pound at St Elizabeth’s psychiatric hospital, Olson felt he was betraying his working class, immigrant background. That discussion group was a rare occurrence, being far from academic, with Gloucesterites of different backgrounds and ages coming together to discuss Ferrini and his relationship to Olson. So, not having found a republic, there was still a place made for poetry in that small city.

Such encounters are becoming rarer: moving from analog to digital interfaces, there are fewer “free” spaces. I think, for example, of W. Eugene Smith’s Jazz Loft Project, a building on 28th st. and 6th Avenue in New York City in which, from 1957 to 1965, all the assumptions about race relations in the US were blown apart by the presence and interaction of the most important musicians in the country. I do still think that the creation of any kind of politics has to begin someplace, literally.

“So, not having found a republic, there was still a place made for poetry in that small city.”

You've said elsewhere that in the postwar years, poets like Robert Duncan & Denise Levertov would mail typewritten manuscripts to one another. Then in the 80's and 90's, correspondences between writers begin to fall away, and the financial margins for the kinds of lives that could have been led in the 50's and 60's start to disappear with the defeat of the US in Vietnam.

Are there available resources within daily life and communication which could release literary culture from its financialized and balkanized state? Olson, who walked away from all institutional life, appears to have spent his final years in poverty– is this kind of renunciation still possible, or necessary, to formulate a response to the political and cultural shifts of our period?

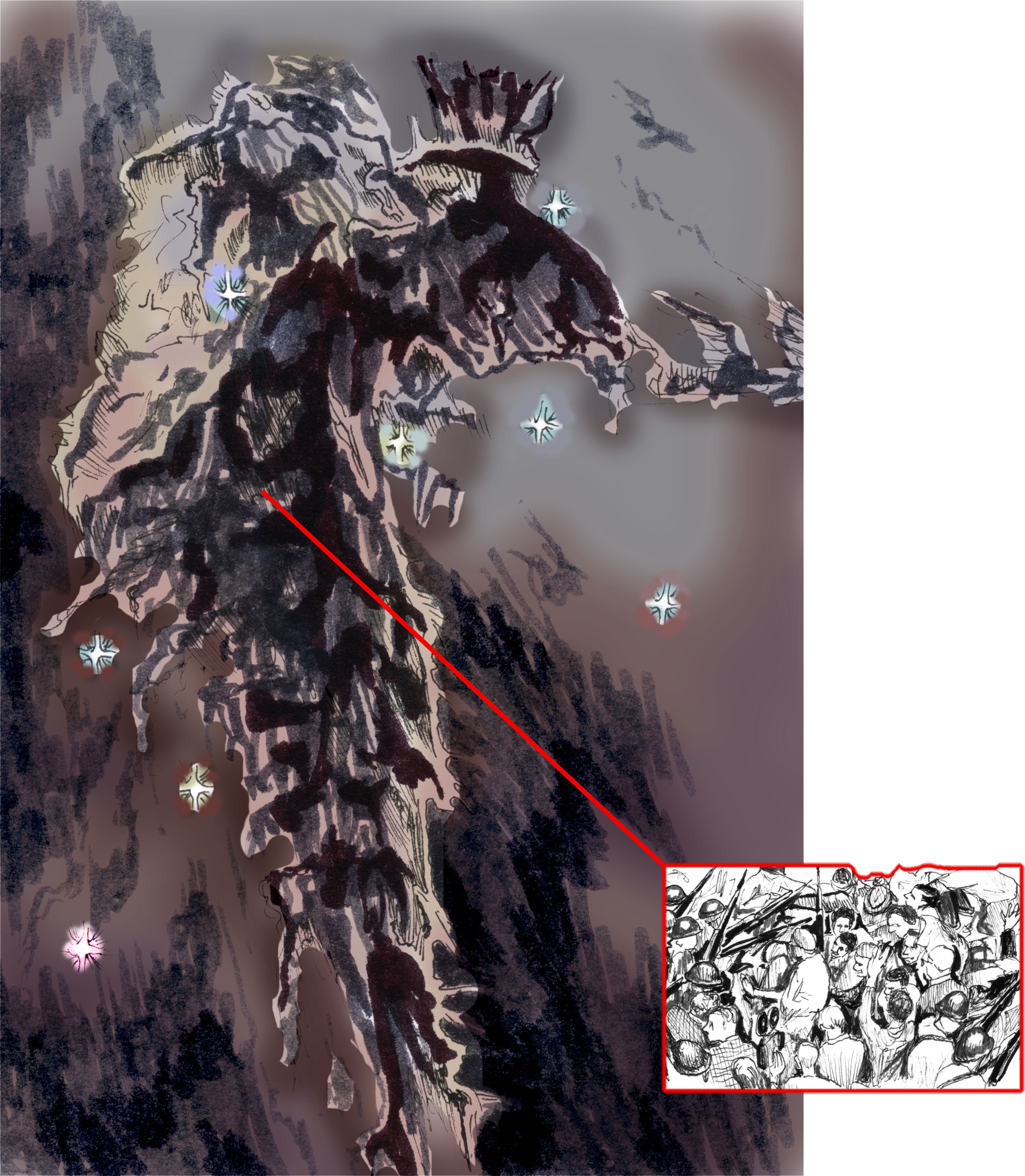

At the 1965 Berkeley Poetry Conference, Olson declares himself “the white man, [...] the ultimate paleface” whose only advantage is that he renounced some actually pretty hard-won privileges, given his own background. Rather than romanticize the past, it’s best to describe it, compare it to the present, and pinpoint the processes that have made conditions so different. By the time Olson died in 1970, the state assassination of Black Panthers’ Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in Chicago, just a month earlier, would be ruled “justifiable homicide.”

Such events mark our current era of mass incarceration. 125 cities burned in the so-called riots of the late 60s, and many of the biggest revolts against the Vietnam War were part of this. The disruption masked the further offshoring of US industry, importation of hard drugs as a form of social and economic control, and a degree of wealth transfer that continues today to levels hardly even imaginable at that time. This is to say nothing so far of the psychotic levels of exceptionalism that allow people to overlook assassinations as part of state structure.

I’m astonished that there are even debates about the political assassinations of the 1960s- a tactic that the people of most countries in the world would simply accept as part of government strategy to retain power and suppress people. Instead of understanding the relationship between state security agencies and the foreign and domestic policies of the US government, we’re now in a situation where the most fervent supporters of the CIA and FBI are liberals for as long as Donald Trump is president because so much of the ideology of exceptionalism has been internalized.

I think renunciation is obligatory and necessary, but it may not be easy to find the right wedges where such gestures can be effective. One problem is the welding of societal spheres, with networked incorporation and disenfranchisement at many levels, making it harder to aim one’s efforts accurately, since so much represents, or is attached to the whole structure. At the same time, many of the tools presently at hand- such as hyper-inflated identity politics- seem to play directly into the hands of the status quo.

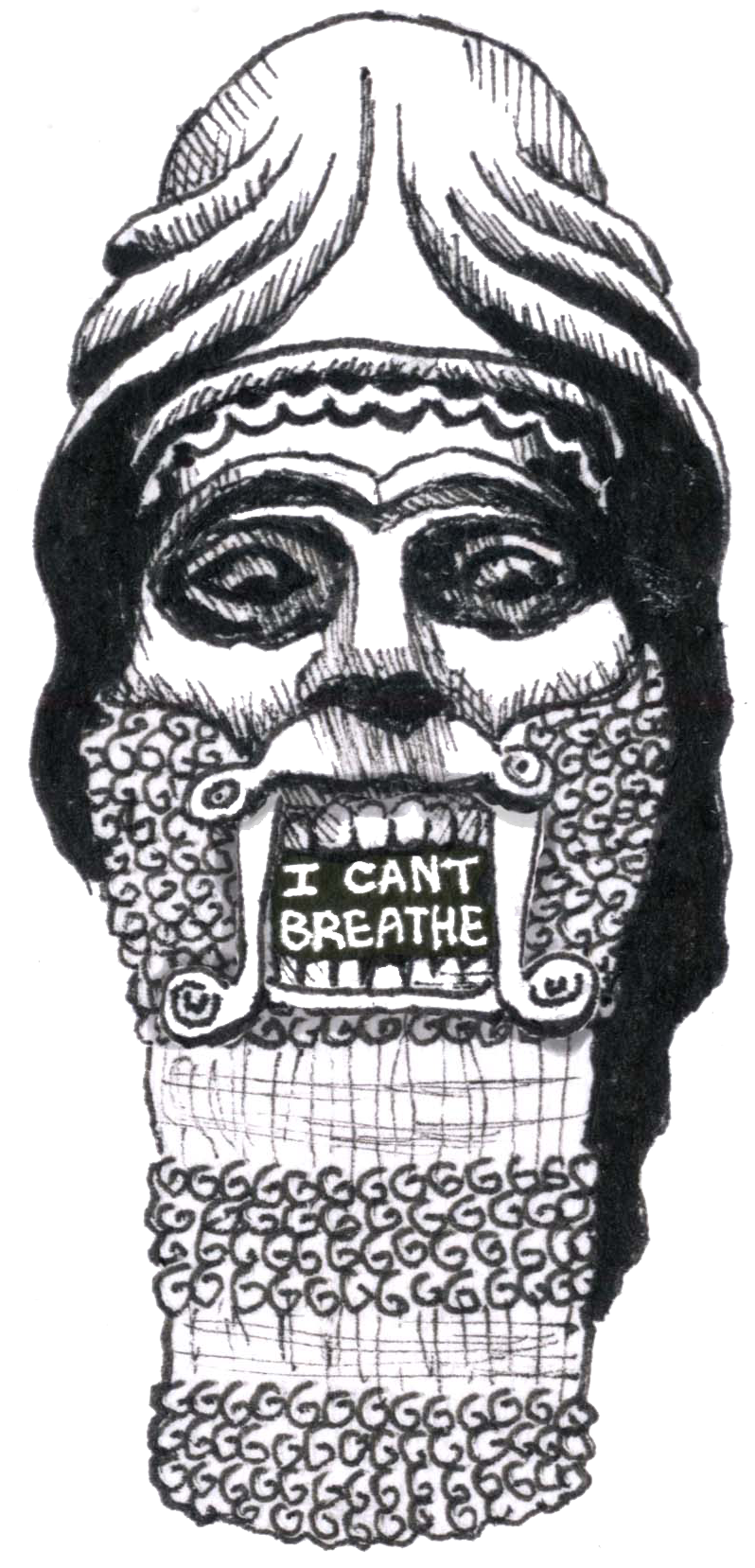

The velocity and flatness of social and digital media make it increasingly difficult to build anything but very easy to destroy– particularly people and history. But there are many approaches to get something done. Amiri Baraka, who increasingly emphasized Olson’s importance in his final years, leaves the legacy of his son Ras, the current Mayor of Newark, though he didn’t live to see it. That resulted from Amiri’s decision to return to his hometown after decades of living elsewhere, to settle there and stick with it, come hell or high water. On the artistic or conceptual front, I think the truest responses to our present state are hidden by those wise enough to know when it’s best to remain under the radar– hard as that may be given its ubiquity.

![]()

LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka

I think renunciation is obligatory and necessary, but it may not be easy to find the right wedges where such gestures can be effective. One problem is the welding of societal spheres, with networked incorporation and disenfranchisement at many levels, making it harder to aim one’s efforts accurately, since so much represents, or is attached to the whole structure. At the same time, many of the tools presently at hand- such as hyper-inflated identity politics- seem to play directly into the hands of the status quo.

The velocity and flatness of social and digital media make it increasingly difficult to build anything but very easy to destroy– particularly people and history. But there are many approaches to get something done. Amiri Baraka, who increasingly emphasized Olson’s importance in his final years, leaves the legacy of his son Ras, the current Mayor of Newark, though he didn’t live to see it. That resulted from Amiri’s decision to return to his hometown after decades of living elsewhere, to settle there and stick with it, come hell or high water. On the artistic or conceptual front, I think the truest responses to our present state are hidden by those wise enough to know when it’s best to remain under the radar– hard as that may be given its ubiquity.

LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka